Sipping the Glengoyne hippie around a campfire on our Beulah trip back in Spring was when Jordan and I first discussed a point-to-point distillery tour. It so happens that the Glengoyne distillery is a short distance from the official start of the popular West Highland Way long-distance hike, which provided us with a route concept to play with. The taste for this idea faded once we were back home, but when Specialized offered to loan us three of their new Sequoia adventure bikes, we penned the last week of October (and British Summer Time) into our sketchbooks – the Scottish Highlands would be oozing autumnal whisky colours at that time of year, we should miss the midges, and the weather might still be kind to us.

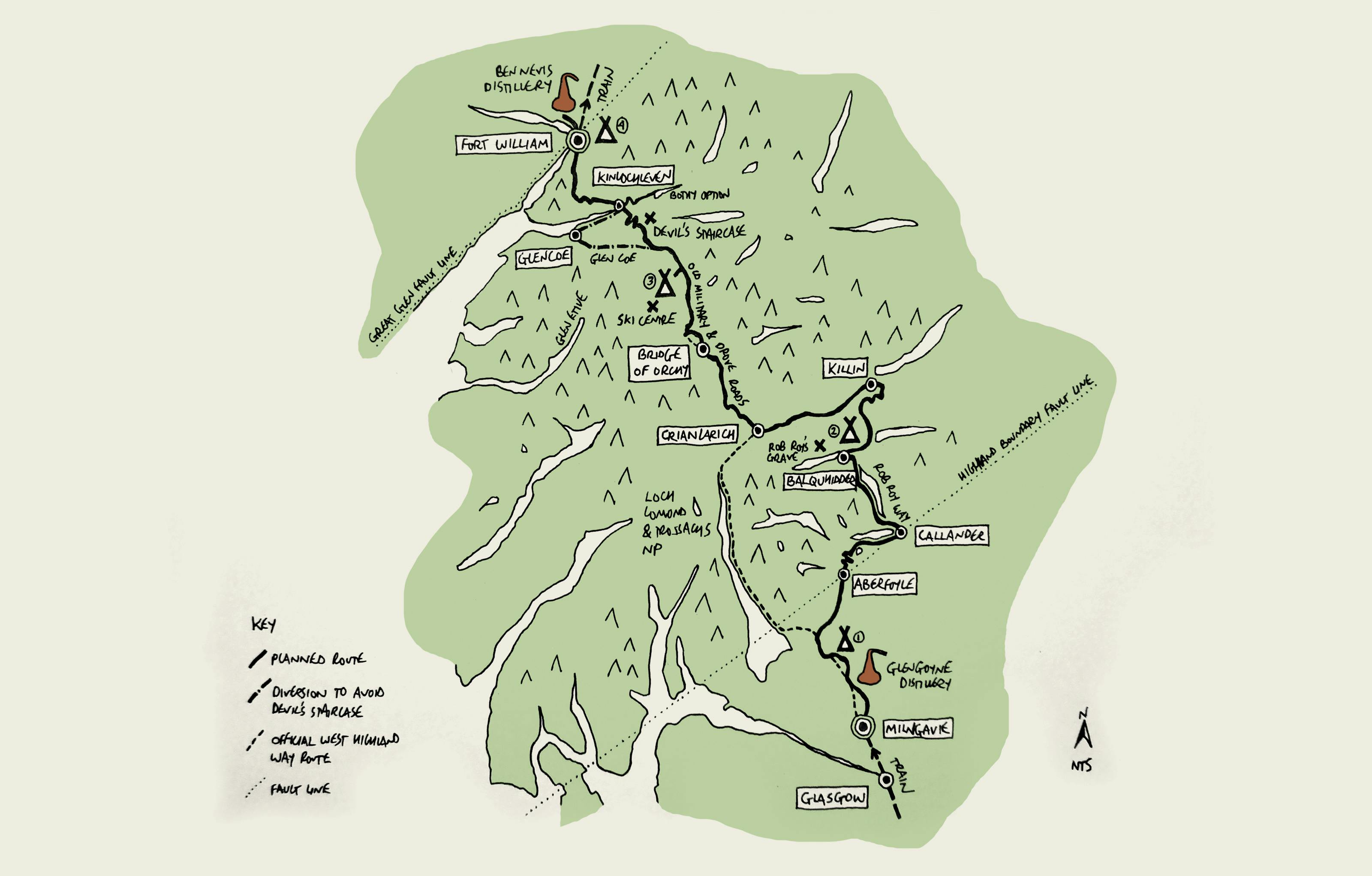

Glyn was keen to join in, and so three of us gave ourselves three days to ride 220km-ish north between two single-malt whisky distilleries: Glengoyne (Lowlands, near Glasgow) and Ben Nevis (Highlands, near Fort William). Our planned route pieced together parts of the Rob Roy and West Highland Ways – a mix of paved roads, forest tracks, and old military / droving roads…

Droving [v]

– the practice of moving goods (typically livestock) over long distances.

– droving to market has a very long history in the Old World, ever since cities found it necessary to source food from distant supplies.

Nestled into Dumgoyne Hill, Glengoyne distillery is a mere 25km from Glasgow, and yet it had something of a charm about it. I could see why the hidden waterfall and its miniature glen shouted out to George Connell, back in 1820, as the ideal location to distil in secret, under the name Glenguin of Burnfoot. He eventually gained a license in 1833 and distilled officially; the name not changing to Glengoyne until 1907. We were still in the Lowlands at this point, but we could see the Highlands lurking on the horizon, rising from Loch Lomond’s waters. We’d be crossing the Highland Boundary Fault Line around Aberfoyle which is when our surroundings would start to really change, thanks to collisions between ancient continents 400 million years ago. This was when both the mountains in much of the Highlands rose and the Central Lowlands sank, creating not only the most important geological division in Scotland but its greatest cultural boundary too – the route we planned was largely created by the military, drovers, and travellers to access the Highlands and travel to/from the more populated Lowlands.

By the time we were propping the bikes against the distillery’s sherry casks to head in for a brief tour and tasting in Warehouse No.1, it was early evening. The “Unhurried since 1833” strapline that adorned their bottles rang true with us, and we ended up chatting with the guys behind the bar (till) and warehouse manager for a while – turns out, back in 1899, the distillery manager had drowned in the on-site loch after a few too many drams. His ghost is still around today, apparently. Anyway, before we had one too many, they sent us on our way with a selection of miniatures – bottles of 10, 15, 18 Year Old – to carry up to Fort William for a tasting session to toast the end of our journey. Loaded up, we rode a bit further north that evening to find somewhere to bed down before the light went; this first night was more of a utility camp so we just set up in a small forest beyond Killearn. For this trip, we had decided on a lightweight shelter setup to stay nimble – we were expecting the odd section of rough terrain and a bike-hike. I took a bivvy bag and tarp, whilst Jordan and Glyn split a two-man Hubba Hubba tent between them. When riding drop bars, frame bags make the ideal place to stick tent and tarp poles, their length tends to nestle nicely underneath the top tube – frame size and geometry dependant, obviously.

“From Crianlarich, we picked up more historic lines of communication: drove roads that Highlanders used to take their cattle to lowland markets, and old military roads that were built to control Jacobite Clans in the 18th Century.”

After a banana nutella porridge and coffee breakfast we rode north to Aberfoyle, stopping only to have a go in the bike park on the outskirts of town. Macgregor’s cafe in the town offered the ideal touring pit stop – a hearty local pie and beans for elevenses providing the fuel we needed to see out the day’s riding up into the Great Forest of Loch Ard and onto somewhere near Balquhidder. At this point, we had diverted from our origins on the West Highland Way and were riding in the tracks of folk hero Rob “Roy” MacGregor (our favourite outlaw) who roamed these parts in the 17th & 18th centuries as he worked, fought, and lived the life of Scotland’s most notorious outlaw. The name Roy comes from Gaelic ‘Ruadh’meaning Red, referring to his red hair – he’d have had an added level of camouflage within our surroundings, at this time of year. Enchanted by the colours, the quiet, and the mirror-like loch waters we could have messed about riding those forest cinder tracks for the rest of the day – it hit home why late autumn is such a good time of the year to be touring.

Our next checkpoint was Balquhidder, where we tracked down the Parish Church on the lower slopes of the north side of the Glen and, in the dark, found Robs Roy’s grave. Under our bike lights, headtorch beams and the drizzle, that churchyard, which still contains the shell of the 1631 church, held a real sense of history and struggle in this stunning but harsh Scottish Highland landscape. He died in 1734, and a recent addition to his grave reads “MacGregor Despite Them!” – a reference to persecution of the clan. We contemplated pitching up somewhere close by, but decided it would be a bit weird so rode further, via a drink in the fancy Mhor 84 restaurant (we were well out of place), on old railway tracks towards Killinuntil we stumbled upon a sheltered camp spot with a picnic bench and, it turned out, a morning view over Loch Earn.

Waking up to heavy rain on a wild camp is a challenge, but exactly what 3-in-1 coffee sachets were made for. Josh, who recently rode from Scotland to Hong Kong, was the first one to justify their place on a touring kitlist to me: an instant easy morning fix, and super space saving. Slightly addictive too, in a bad way. We struck camp as quick as possible, knowing we’d try and stay somewhere that night so would be able to dry out our badly packed camping kit. As with anything, it’s that first step of getting out there that is the hardest; once we’d set off riding we didn’t notice or mind the horizontal rain stabbing us in the eyes as much, we could only get so wet. Upon reaching Crianlarich, we joined back up with the Wet West Highland Way. It continued raining hard all morning so we took some time out in the hotel there to eat, dry, and warm up. It was from this point that we would join the more historic lines of communication: droving roads that Highlanders used to take their cattle to lowland markets, and military roads that were built to control Jacobite Clans. The three of us were excited to head more off the beaten track, and noticing a break in the rain, we packed up the rest of our Highlander Pizza (it had a bit of Haggis on top) into a pizza box, strapped it to the top of my seatpack, and made the most of the dry daylight hours, pedalling off to start what, from our OS map, looked like an awesome section: the Droving Road to Glencoe.

“What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wilderness? Let them be left,

O Let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet”

During the 1700’s, a network of military roads was conceived by Generals Wade and Caulfeild, totalling around 1050 miles, to allow Government forces to access key locations in the Highlands in case of Jacobite uprisings. There were often pre-existing tracks along much of the routes made by drovers and travellers – some of which were used and improved by the military roads. However, new stretches were made where deemed necessary, like the zig-zags of Devil’s Staircase to Kinlochleven. The military road that the West Highland Way follows, between Stirling and Fort William, was started in 1748 and took several years to complete. The roads tended to be built from local stone and gravel, with a graded base 4.9m wide topped with a 3m wide roadway. However, given the wear & tear and adverse weather, by the end of the 1700’s these military roads were falling into a state of disrepair, and so their suitability for increasing levels of commercial traffic was in question.

In 1803, the government under the Commission for Highland Roads and Bridges, asked Thomas Telford to build new roads and bridges in the Highlands – including this Droving Road to Glencoe.

This section turned out to be the most memorable few kms of our journey, and a good test for the Sequoia bikes as the track started off on close-knit cobbles and ended in chunky rock and gravel as it rose up to 450m, before descending into the glen. Expect some real fun riding across wide open moorland amongst big surrounding peaks, old stone bridges over small brooks and gorges, ruins, and areas of forest. This old road went out of use as a main public route in 1933, and is now maintained for estate access, and the West Highland Way.

With a spare hour-or-so of daylight left, and only a couple of kms to the Glencoe Mountain Centre, we opted to take the slight detour to a ruin marked on the OS map for a somewhat sheltered hot drink, Jamaican Ginger Cake, and pizza leftovers break in the middle of nowhere…

To recoup after a couple of days on the road wild camping, we stopped over in a cabin at the desolate Glencoe Mountain Centre; the end of October clearly wasn’t a busy time for them. This year (2016) they celebrated their 60th anniversary as Scotland’s first ski centre. Phillip Rankin ‘the Scottish skiing pioneer’ alongside a couple of other members of the Scottish Ski Club opened the lift at White Corries in 1956. Roger Cox, in the Scotsman, explains that “many of the people involved in the project, including Rankin, had fought in the Second World War, and they approached a series of apparently insurmountable problems (like building a ski centre in Scotland) with an admirable, anything-is-possible attitude. No ski resorts in Scotland? Fine, let’s build one. We need permission to build one there? Fine, let’s ask the landowner. We need to move a load of heavy machinery almost to the summit of a steep, rocky, boggy Munro? No problem.” Today, with seven lifts and nineteen runs, this is not the largest resort but there are also downhill tracks and trails for riders…

That night we met the first people we’d seen out walking the West Highland Way, two friends – a Polish and a Belgian student from Stirling University – taking shelter in the warm dry toilet block, well away from their cheap pop-up tent pitched outside in the gales and rain. They had two days left of the hike but, by the sounds of it, they could’ve done with it being their last. For them, Fort William was still 35km away on foot, which highlighted one of the better things about travelling by bike – slow enough to immerse ourselves in places, but fast enough to cover distances and change plans.

As our camp kit dried, we ourselves spread the OS maps over the floor to check out our options for the last day-and-a-bit, given the weather hammering the cabin. Our original idea was to head over Devil’s Staircase to Kinlochleven and ride/hike to the MBA bothy just east of Kinlochleven on Loch Eilde Mor. However, as amazing as this night could have been, it was at least 5km down an unknown boggy path which would have left us with a super sketchy timeframe to make our train home from Fort William, at 11.00am on the final morning. The weather didn’t help with our optimism either – there was a printout of the mountain weather forecast on the bar noticeboard – so Plan B Touring kicked in. We would head to stay in Fort William tomorrow night, check out Devil’s Staircase, but potentially return to stay down at the bottom of the glen, through Glencoe village and round to Kinlochleveninstead if the weather and visibility was bad; we didn’t want to be ‘those guys stuck on the hill’.

As soon as the light rose the next morning, we packed the bikes and gave the downhill run a go before continuing down the glen towards Altnafeadh, where the track kicked up to Devil’s Staircase (a supposed route used in the Glencoe Massacre of 1692). At points, we could not see much further than 100m through the rain, wind and mist; the photos don’t do it justice. We progressed a fair way towards Kinlochleven, mainly hiking with the bikes, before deciding that it wasn’t the day for heading into the hills and so turned back to ride through Glen Coe, a more suitable route on the Sequoia bikes. This Glen Coe route was stunning anyway – the random white farmhouse providing the only scale in an otherwise epic and super moody Munro landscape – our detour in no way felt like a setback. The only reference to the Glencoe Massacre we noticed was at the awesome Clachaig Inn on the backroad to Glencoe village – a droving stop-off, and now a popular climbers pub, which has a sign on its door saying “No Hawkers or Campbells”. From Kinlochleven, it was back on the Old Military Roads to Fort William where, after a couple of beers and live music at the Grog and Gruel pub in town, we stopped over at the Backpackers Hostel, just a couple of kms away from our final calling point: the Ben Nevis Distillery.

“There are some who would have you believe that there exists a kind of divine secret, a miraculous ingredient or genius behind the manufacture of Scotch Whisky. I however, acknowledge no miracle other than that which is worked when science and nature combine…

…The principal ingredients are three, notably water, barley and yeast, with a measure of peat smoke or reek. Of these there can be no doubt that water is the foremost. On Ben Nevis I was fortunate to find a constant and consistent source of pure clean water in two small lochans. In order of importance, the second ingredient is barley. This must be clean and plump, fully rounded and quite dry, containing exactly the right amount of protein. Special distiller’s yeast is the third ingredient. This has the texture of dough or putty and is vital to the process of fermentation. And fourthly there is peat, which comes to the whisky through the water passing over peat bogs on its way down the mountain, and from the ‘reek’ from the fire lit during the manufacturing process. Once again, we are fully fortunate in that nature in her magnificence has created on the hill behind us, an ample supply of peat in our own banks to fuel the fires drying the barley.”

John MacDonald

Ben Nevis Distillery, 14th June 1827

The Ben Nevis distillery of today was a real contrast to Glengoyne. Although it has the impressive mountain backdrop, it is not quite the same arriving off of a busy main road. The distillery has a much more industrial feel, the ‘angel’s share’ (evaporated whisky) stained all the distillery sheds in black mould; it lacked the quaint charm of our start point distillery in the Lowlands. However, it was rewarding to reach the planned end point for the trip, not least because it signalled the start of our brief tasting session before jumping on the train home. The Glengoyne bottles had just about made it intact after a bumpy three days on the road, and looked the more authentic for it. Boy, did it taste good; better than around the campfire on our Beulah Tour – the super smooth whisky had an added relevance now.

Sitting on the train back, it was awesome to retrace our tyre tracks for a lot of the route down to Crianlarich, and seek out new routes from the window – Corrour Station was definitely somewhere to return with our loaded adventure bikes at some point. One thing was clear: whatever the reason behind the original lines of communication, we owe it to the people who established, trod, built and maintain the roads and tracks that enable us to access these stunning places. The increasingly popular breed of adventure bikes, like the Specialised Sequoia, are the ideal fun machines for this type of trip, but without any sort of basic track, we would be walking most of the way…